All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

There's a new method of restoring vision

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

">

">Biologists have managed to insert the gene for the light-sensitive protein substance MCO1 into the retinal nerve cells of rodents that have lost their sight.

The researchers inserted a gene into a viral object and introduced it into the visual organs of mice suffering from retinitis pigmentosa. The new protein substance did not provoke an inflammatory response, and the rodents successfully passed the visual testing.

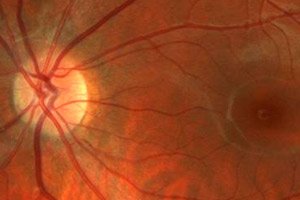

During the perception of the image visible to the eye, light rays are focused in the area of the retina, equipped with photoreceptors - the well-known cones and rods. The receptors contain a photosensitive protein opsin, which reacts to the photon flow and causes intrareceptor generation of a nerve impulse. The impulse is transmitted to the bipolar nerve cells of the retina, after which it is sent to the brain.

But such a scheme does not always work: in patients with retinitis pigmentosa (there are about 1.5 million of them in the world), photoreceptors lose the ability to react to light, which is associated with changes in the genes of photosensitive opsins. This hereditary pathology causes a strong decline in visual function, up to complete loss of vision.

Drug therapy for retinitis pigmentosa is complex and does not involve restoration, but only the preservation of the functional capacity of the remaining "surviving" receptors. For example, retinol acetate preparations are actively used. Vision can only be restored by complex and expensive surgical intervention. However, optogenetic methods have recently come into practice: specialists embed photosensitive protein substances directly into the retinal nerve cells, after which they begin to respond to the light flux. But before the current study, a response from genetically modified cells could only be obtained after a powerful signal effect.

Scientists introduced a substance that reacts to daylight into bipolar nerve cells. A DNA fragment was created to highlight opsin, which was then introduced into a viral particle that had lost its pathogenic properties: its purpose was to deliver and package it into a genetic construct. The particle was injected into the eye of a sick rodent: the DNA fragment was integrated into the neurons of the retina. Under microscopic control, scientists noticed that the genes reached the limit of activity by the 4th week, after which the level stabilized. To check the quality of vision after the procedure, the rodents were given a task: to find a dry illuminated island in the water, while being in the dark. The experiment demonstrated that the mice's vision really and significantly improved already in the 4th-8th week after the manipulation.

It is quite possible that the developed gene therapy of the rodent retina will be adapted for treating people after a series of other tests. If this happens, there will be no need for expensive surgical interventions, or for connecting special devices to amplify the photo signal. Only one or several injections of protein substance will be required.

More details about the study can be found in the journal Gene Therapy and on the Nature page