All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

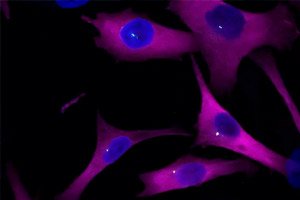

Discovery of melanoma's 'cellular compass' could help stop metastasis

Last reviewed: 03.08.2025

Researchers have discovered a protein that plays a key role in guiding melanoma cells as they spread throughout the body. The cancer cells become dependent on this protein to migrate, pointing to new strategies for preventing metastasis.

The eIF2A protein is typically thought to be activated when cells are stressed and help ribosomes trigger protein synthesis. But according to a study published in Science Advances, eIF2A has a completely different role in melanoma — it helps cancer cells control their movement.

“Cancerous cells that metastasize need to move through tissues to reach nearby or distant organs. Targeting eIF2A could be a new strategy to prevent melanoma from breaking away and forming tumors in other locations,” says Dr. Fatima Gebauer, corresponding author of the study and a researcher at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona.

Although melanoma accounts for only a small proportion of skin cancer cases, it kills nearly 60,000 people worldwide each year. The five-year survival rate for localized melanoma is about 99%, while for metastatic melanoma, especially with distant spread, it is much lower - about 35%. Understanding the mechanisms of malignant cell metastasis is essential to improving medical care.

Working with two parallel lines of human skin cells that differ only in their metastatic potential, the team weakened eIF2A function. In the cancer cells, the growth of three-dimensional tumor spheres stopped and migration through a scratch in culture was slowed. However, protein synthesis was barely affected, disproving the idea that eIF2A triggers protein synthesis.

To find an alternative function, the researchers extracted eIF2A from the cell using molecular fishing and catalogued its protein partners. Many of them turned out to be components of the centrosome, a molecular structure that organizes microtubules and guides cells as they move. In the absence of eIF2A, the centrosome often pointed in the wrong direction when cells tried to move forward.

Further experiments showed that eIF2A works to preserve parts of the centrosome so that it points the cell in the right direction as it moves. The protein's tail is critical to the cell's ability to migrate. Trimming the tail reduced the cell's ability to move and could be a potential drug target.

"The tail acts like scaffolding cement, holding key parts of the melanoma cellular compass in place so that malignant cells can navigate and leave the primary tumor," said Dr. Jennifer Jungfleisch, first author of the study.

The study authors note that eIF2A dependence only occurs after malignant transformation, suggesting a therapeutic window that can spare healthy tissue. However, more research is needed to understand how disruption of this protein works in tissues and animal models.

"In many cases, potential therapeutic targets are either redundant or essential for normal cells, but the discovery of a protein that only becomes essential during metastasis may be a rare find. Any potential vulnerability is important," concludes Dr. Gebauer.