All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Esophageal atresia

Medical expert of the article

Last reviewed: 12.07.2025

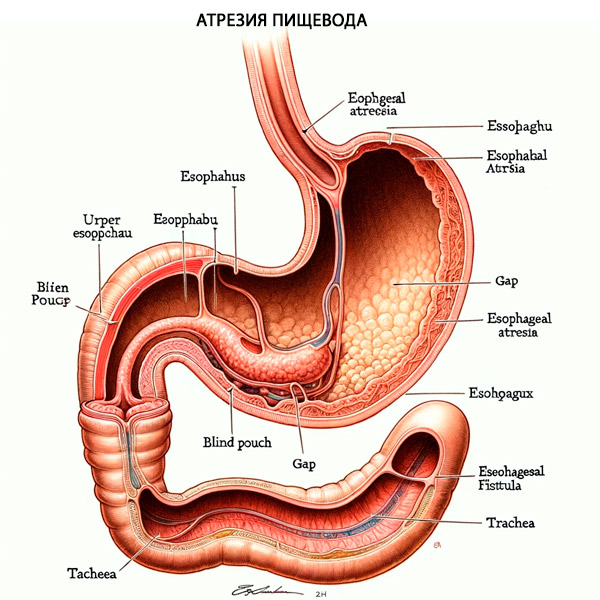

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a congenital malformation in which the esophagus ends blindly at a distance of approximately 8-12 cm from the entrance to the oral cavity.

Congenital tracheoesophageal fistula without atresia is a pathological channel lined with granulation tissue or epithelium, communicating the unchanged lumen of the esophagus with the lumen of the trachea.

Esophageal atresia is the most common type of gastrointestinal atresia.

Epidemiology

Esophageal atresia is a congenital malformation of the upper gastrointestinal tract with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 4,500 births.[ 1 ] In the United States, the prevalence is estimated to be 2.3 per 10,000 live births.[ 2 ] The relative incidence of esophageal atresia increases with maternal age.[ 3 ],[ 4 ]

Causes esophageal atresia

The etiology of esophageal atresia with or without associated tracheoesophageal fistula is failure to separate or incompletely develop the foregut.[ 5 ] The fistula tract originates from a branch of the embryonic lung rudiment that fails to branch due to defective epithelial-mesenchymal interactions.

Several genes have been associated with esophageal atresia, including Shh, [ 6 ] SOX2, CHD7, MYCN, and FANCB. However, the etiology is not fully understood and is likely multifactorial. Patients may be diagnosed with either isolated AP/TPS or part of a syndrome such as VACTERL or CHARGE.

Pathogenesis

The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports the food bolus from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus originates from the germinal layer of endoderm that forms the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and epithelial lines of the aerodigestive tract. The trachea and esophagus arise from the division of a common foregut tube early in fetal development. [ 7 ] Failure to separate or fully develop this common foregut tube may result in tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) and esophageal atresia (EA). Prenatally, patients with esophageal atresia may present with polyhydramnios, predominantly in the third trimester, which may be a diagnostic clue to esophageal atresia.

Additionally, approximately 50% of patients with TPS/EA will have associated congenital anomalies including VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb anomalies) or CHARGE ( coloboma, cardiac defects, choanal atresia, growth retardation, genital anomalies, and ear anomalies). After birth of the neonate, the most common symptoms of esophageal atresia are excessive salivation, choking, and inability to pass a nasogastric tube. Additionally, if there is associated TPS, gastric distension will occur as air passes from the trachea through the distal esophageal fistula and then into the stomach.

Patients with this symptom complex should undergo expedited evaluation for esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula and prompt referral to a higher level of care for evaluation by a pediatric surgeon.

Pathophysiology

Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia result from defective lateral division of the foregut into the esophagus and trachea. The fistula tract between the esophagus and trachea may form secondarily due to defective epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. [6] Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia are present together in approximately 90% of cases. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula are classified into 5 categories based on their anatomical configuration. [ 8 ]

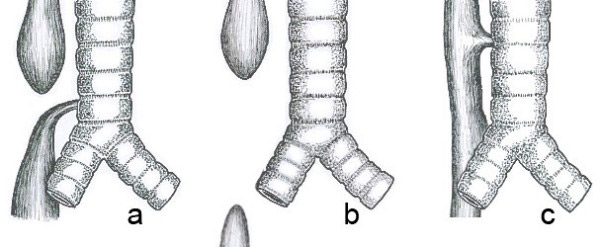

- Type A is isolated esophageal atresia without associated tracheoesophageal fistula, the prevalence of which is 8%.

The proximal and distal esophagus end blindly and are not connected to the trachea. The proximal esophagus is dilated, thick-walled, and usually ends higher in the posterior mediastinum, near the second thoracic vertebra. The distal esophagus is short and ends at variable distances from the diaphragm. The distance between the two ends will determine whether primary repair is possible (rare) or whether delayed primary anastomosis or esophageal replacement should be performed. In these cases, it is important to exclude a proximal tracheoesophageal fistula.

- Type B is esophageal atresia with proximal tracheoesophageal fistula. This is the rarest type, with a prevalence of 1%.

This rare anomaly must be distinguished from the isolated variety. The fistula is not located at the distal end of the upper sac, but 1–2 cm above its end on the anterior wall of the esophagus.

- Type C esophageal atresia is the most common (84-86%) and involves proximal esophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula.

This is an atresia in which the proximal esophagus is dilated and the muscular wall thickened, terminating blindly in the superior mediastinum at about the level of the third or fourth thoracic vertebra. The distal esophagus, which is thinner and narrower, enters the posterior wall of the trachea at the carina or, more commonly, one to two centimeters proximal to the trachea. The distance between the blind proximal esophagus and the distal tracheoesophageal fistula varies from overlapping segments to a wide slit. Very rarely, the distal fistula may be occluded or obliterated, leading to a misdiagnosis of isolated atresia before surgery.

- Type D - esophageal atresia with proximal and distal tracheoesophageal fistula, rare - about 3%

In many of these infants, the anomaly was misdiagnosed and treated as proximal atresia and distal fistula. As a result of recurrent respiratory infections, a tracheoesophageal fistula, previously mistaken for a recurrent fistula, was identified on examination. With the increasing use of preoperative endoscopy (bronchoscopy and/or esophagoscopy), the "double" fistula can be recognized early and fully repaired during the initial procedure. If a proximal fistula is not identified preoperatively, the diagnosis should be suspected by a large gas leak originating from the upper pouch during anastomosis.

- Esophageal atresia type E is an isolated tracheoesophageal fistula without associated esophageal atresia. It is known as type "H" and has a prevalence of about 4%.

There is a fistula connection between the anatomically intact esophagus and the trachea. The fistula tract can be very narrow, 3–5 mm in diameter, and is usually located in the lower cervical region. They are usually single, but two or even three fistulas have been described.

Common anatomical types of esophageal atresia. a) Esophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula (86%). b) Isolated esophageal atresia without tracheoesophageal fistula (7%). c) H-type tracheoesophageal fistula (4%)

Symptoms esophageal atresia

In approximately one third of fetuses, esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula are diagnosed prenatally. The most common sonographic sign of esophageal atresia is polyhydramnios, which occurs in approximately 60% of pregnancies. [ 9 ] If diagnosed prenatally, the family can be counseled about postnatal expectations.

However, in many cases the diagnosis is not made until birth. Infants with esophageal atresia present with symptoms shortly after birth, with increased secretions leading to choking, respiratory distress, or episodes of cyanosis during feeding. In esophageal atresia, a fistula between the trachea and distal esophagus results in the stomach filling with gas on chest radiograph. Infants with types A and B esophageal atresia will not have abdominal distension because there is no fistula from the trachea to the distal esophagus. Infants with a tracheoesophageal fistula may reflux stomach contents through the fistula into the trachea, leading to aspiration pneumonia and respiratory distress. In patients with type E esophageal atresia, diagnosis may be delayed if the fistula is small.[ 10 ]

Where does it hurt?

What's bothering you?

Forms

There are about 100 known variants of this defect, but three of the most common are:

- esophageal atresia and fistula between the distal esophagus and trachea (86-90%),

- isolated esophageal atresia without fistula (4-8%),

- tracheoesophageal fistula, type H (4%).

In 50-70% of cases of esophageal atresia, there are combined developmental defects:

- congenital heart defects (20-37%),

- gastrointestinal tract defects (20-21%),

- defects of the genitourinary system (10%),

- musculoskeletal defects (30%),

- craniofacial defects (4%).

In 5-7% of cases, esophageal atresia is accompanied by chromosomal abnormalities (trisomy 18, 13 and 21). A peculiar combination of developmental abnormalities in esophageal atresia is designated as "VATER" by the initial Latin letters of the following developmental defects (5-10%):

- spinal defects (V),

- anal defects (A),

- tracheoesophageal fistula (T),

- esophageal atresia (E),

- radius bone defects (R).

30-40% of children with esophageal atresia are premature or have intrauterine growth retardation. [ 11 ], [ 12 ]

Complications and consequences

Surgical complications may occur after repair of esophageal atresia. The most feared complication is esophageal anastomotic leak.[ 13 ] Small leaks may be treated with chest tube drainage and prolonged NPO until the leak is corrected. If there is a large leak or anastomotic leak, reoperation and esophageal resection with interposition of a gastric, colonic, or jejunal graft may be required.

Another potential complication is esophageal anastomotic stricture. These are usually treated with serial endoscopic esophageal dilations.[ 14 ] Finally, although rare, recurrent fistulization of the esophagus and trachea has been reported. These problems are treated with reoperation.

Non-surgical complications of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula are common. The use of proton pump inhibitors is recommended for at least one year after repair of esophageal atresia due to esophageal dysmotility, which leads to increased gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and risk of aspiration.[ 15 ] Tracheomalacia is commonly seen after surgery. Neonates with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula typically have an increased incidence of dysphagia, respiratory tract infections, and esophagitis.[ 16 ]

Because of elevated GER in childhood and adulthood, these children have a higher incidence of Barrett's esophagus and a higher risk of esophageal cancer compared with the general population.[ 17 ]Esophageal cancer screening protocols are recommended in these patients, although this is controversial.

Diagnostics esophageal atresia

Esophageal atresia is usually diagnosed when an orogastric tube cannot be passed. The tube does not extend to the stomach and may be seen coiled above the level of the esophageal atresia on chest radiograph. Definitive diagnosis can be made by injecting a small amount of water-soluble contrast medium into the orogastric tube under fluoroscopic guidance. Barium should be avoided because it can cause chemical pneumonitis if aspirated into the lungs.Esophagoscopy or bronchoscopy to detect a tracheal fistula may be used to confirm the diagnosis.[ 18 ]

A newborn with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula requires evaluation for VACTERL and CHARGE anomalies, as they may occur in up to 50% of newborns. Specifically, a complete evaluation requires a cardiac echocardiogram, radiographs of the extremities and spine, renal ultrasound, and a thorough physical examination of the anus and genitals for any abnormalities. A large single-center study in the United States examined the most common congenital anomalies associated with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Among nearly 3,000 patients, associated VACTERL diagnoses included spinal anomalies in 25.5%, anorectal malformations in 11.6%, congenital heart defects in 59.1%, renal disease in 21.8%, and limb defects in 7.1%. [ 19 ] Almost one third had 3 or more anomalies and met the criteria for a VACTERL diagnosis.

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include laryngeal, tracheal, and esophageal clefts, esophageal septa or rings, esophageal strictures, tubular esophageal duplications, congenital short esophagus, and tracheal agenesis. These diagnoses can be further investigated using a variety of imaging techniques, ranging from X-rays and CT scans to endoscopy and surgery.

Who to contact?

Treatment esophageal atresia

Once the diagnosis of esophageal atresia is made, the infant should be intubated to control the airway and prevent further aspiration. If not already done, a catheter should be gently inserted to suction out oropharyngeal secretions. The infant should be given antibiotics, IV fluids, and nothing by mouth. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be considered for the infant. Once the infant is hemodynamically and airway stabilized, a pediatric surgeon should be consulted.

The timing of definitive surgical treatment of esophageal atresia depends on the size of the infant. If the infant weighs more than 2 kilograms, surgery is usually offered after correction of cardiac anomalies, if present. Very low birth weight infants (<1500 grams) are usually treated in a staged manner with initial ligation of the fistula followed by repair of the esophageal atresia as the infant grows larger.[ 20 ]

Surgical options for repair of esophageal atresia include open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.[ 21 ] The steps are the same in both surgeries. The fistula between the esophagus and trachea is identified and divided. A bronchoscope can be used to visualize the origin of the fistula in the trachea. Once the fistula is ligated, the esophageal atresia is repaired. Typically, a small nasogastric tube is placed to cross the two ends, and the ends are sutured with absorbable suture if the ends can be reached without too much tension. If the ends of the esophagus are under too much tension or cannot be reached, the Foker technique can be used.[ 22 ] This technique uses traction sutures on the ends of the esophagus and slowly brings them together. Once the ends come together without tension, the primary repair can be performed.

If there is an extra-long esophageal tear that precludes primary anastomosis, then insertion of another organ such as the stomach, colon, or jejunum may be used.[ 23 ] Patients with type E "H-type" esophageal atresia may be treated with a high cervical incision and avoid thoracotomy for fistula ligation.[ 24 ] Gastrostomy is usually not indicated unless primary anastomosis has failed.

Following surgery, the infant is returned to the neonatal intensive care unit for close observation. A chest tube is left in place on the side where the chest was accessed. The infant continues to receive total parenteral nutrition via a nasogastric tube with intermittent suctioning. Esophagography is performed after 5 to 7 days to check for esophageal leakage. If no leak is found, oral feedings are usually started. If a leak is present, the chest tube will collect the drainage. The chest tube is left in place until the leak closes and/or the infant tolerates oral feedings.

Forecast

The prognosis for neonates with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula is relatively good and depends mainly on the cardiac and chromosomal abnormalities rather than the esophageal atresia itself. Generally, overall survival is around 85–90%.[ 25 ] Higher mortality is seen when concomitant cardiac anomalies are present in addition to esophageal atresia. Early deaths are associated with cardiac anomalies, whereas late deaths are associated with respiratory complications. The distance between the two esophageal pouches, especially if large, may determine the prognosis.[ 26 ] All neonates undergoing repair of esophageal atresia will have expected gastrointestinal and respiratory problems, which usually improve with age.

Sources

- Nasr T, Mancini P, Rankin SA, Edwards NA, Agricola ZN, Kenny AP, Kinney JL, Daniels K, Vardanyan J, Han L, Trisno SL, Cha SW, Wells JM, Kofron MJ, Zorn AM. Endosome-Mediated Epithelial Remodeling Downstream of Hedgehog-Gli Is Required for Tracheoesophageal Separation. Dev Cell. 2019 Dec 16;51(6):665-674.e6.

- Pretorius DH, Drose JA, Dennis MA, Manchester DK, Manco-Johnson ML. Tracheoesophageal fistula in utero. Twenty-two cases. J Ultrasound Med. 1987 Sep;6(9):509-13.

- Cassina M, Ruol M, Pertile R, Midrio P, Piffer S, Vicenzi V, Saugo M, Stocco CF, Gamba P, Clementi M. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of children with esophageal atresia: A 32-year population-based study including 1,417,724 consecutive newborns. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016 Jul;106(7):542-8.

- Karnak I, Senocak ME, Hiçsönmez A, Büyükpamukçu N. The diagnosis and treatment of H-type tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Dec;32(12):1670-4.

- Scott D.A. Esophageal Atresia / Tracheoesophageal Fistula Overview – RETIRED CHAPTER, FOR HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle (WA): Mar 12, 2009.

- Crisera CA, Grau JB, Maldonado TS, Kadison AS, Longaker MT, Gittes GK. Defective epithelial-mesenchymal interactions dictate the organogenesis of tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16(4):256-61.

- Spitz L. Oesophageal atresia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007 May 11;2:24.

- Lupo PJ, Isenburg JL, Salemi JL, Mai CT, Liberman RF, Canfield MA, Copeland G, Haight S, Harpavat S, Hoyt AT, Moore CA, Nembhard WN, Nguyen HN, Rutkowski RE, Steele A, Alverson CJ, Stallings EB, Kirby RS., and The National Birth Defects Prevention Network. Population-based birth defects data in the United States, 2010-2014: A focus on gastrointestinal defects. Birth Defects Res. 2017 Nov 01;109(18):1504-1514.

- Clark DC. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Am Fam Physician. 1999 Feb 15;59(4):910-6, 919-20.

- Lautz TB, Mandelia A, Radhakrishnan J. VACTERL associations in children undergoing surgery for esophageal atresia and anorectal malformations: Implications for pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Aug;50(8):1245-50.

- Petrosyan M, Estrada J, Hunter C, Woo R, Stein J, Ford HR, Anselmo DM. Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula in very low-birth-weight neonates: improved outcomes with staged repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Dec;44(12):2278-81.

- Patkowsk D, Rysiakiewicz K, Jaworski W, Zielinska M, Siejka G, Konsur K, Czernik J. Thoracoscopic repair of tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009 Apr;19 Suppl 1:S19-22.

- Foker JE, Linden BC, Boyle EM, Marquardt C. Development of a true primary repair for the full spectrum of esophageal atresia. Ann Surg. 1997 Oct;226(4):533-41; discussion 541-3.

- Bairdain S, Foker JE, Smithers CJ, Hamilton TE, Labow BI, Baird CW, Taghinia AH, Feins N, Manfredi M, Jennings RW. Jejunal Interposition after Failed Esophageal Atresia Repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Jun;222(6):1001-8.

- Ko BA, Frederic R, DiTirro PA, Glatleider PA, Applebaum H. Simplified access for division of the low cervical/high thoracic H-type tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2000 Nov;35(11):1621-2. [PubMed]

- 16.

- Choudhury SR, Ashcraft KW, Sharp RJ, Murphy JP, Snyder CL, Sigalet DL. Survival of patients with esophageal atresia: influence of birth weight, cardiac anomaly, and late respiratory complications. J Pediatr Surg. 1999 Jan;34(1):70-3; discussion 74.

- Upadhyaya VD, Gangopadhyaya AN, Gupta DK, Sharma SP, Kumar V, Pandey A, Upadhyaya AD. Prognosis of congenital tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia on the basis of gap length. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007 Aug;23(8):767-71.

- Engum SA, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR. Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 227 cases of esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula over two decades. Arch Surg. 1995 May;130(5):502-8; discussion 508-9.

- Antoniou D, Soutis M, Christopoulos-Geroulanos G. Anastomotic strictures following esophageal atresia repair: a 20-year experience with endoscopic balloon dilatation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Oct;51(4):464-7.

- Krishnan U, Mousa H, Dall'Oglio L, Homaira N, Rosen R, Faure C, Gottrand F. ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Esophageal Atresia-Tracheoesophageal Fistula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Nov;63(5):550-570.

- Connor MJ, Springford LR, Kapetanakis VV, Giuliani S. Esophageal atresia and transitional care--step 1: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature to determine the prevalence of chronic long-term problems. Am J Surg. 2015 Apr;209(4):747-59.

- Jayasekera CS, Desmond PV, Holmes JA, Kitson M, Taylor AC. Cluster of 4 cases of esophageal squamous cell cancer developing in adults with surgically corrected esophageal atresia--time for screening to start. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 Apr;47(4):646-51.