All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Endometritis

Medical expert of the article

Last reviewed: 04.07.2025

Endometritis is an infectious inflammation of the endometrium that, if not properly diagnosed and treated, can cause severe long-term complications in women. Diagnosis of endometritis can be difficult and is often underdiagnosed due to the wide range of potential clinical features. Treatment requires accurate and prompt recognition of the condition, appropriate antibiotics, and coordination between multidisciplinary specialists. [ 1 ]

Endometritis is an inflammation localized in the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, most often of infectious etiology. [ 2 ] An infection that spreads to the fallopian tubes, ovaries, or pelvic peritoneum is called pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). [ 3 ] Endometritis is traditionally divided into 2 types: acute and chronic. Postpartum endometritis is a subtype of acute endometritis associated with pregnancy. [ 4 ], [ 5 ]

Epidemiology

Acute endometritis

The incidence of acute endometritis alone is challenging because it often occurs in the setting of PID, the incidence of which is approximately 8% in the United States (US) and 32% in developing countries.[ 6 ] Cases of PID in the US are often associated with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, accounting for 50% of such cases.[ 7 ]

Chronic endometritis

Given the generally mild presentation, the true prevalence of chronic endometritis is difficult to estimate. Some studies have shown that in people with recurrent miscarriage, the incidence is nearly 30%. However, the incidence varies even within the same study depending on the menstrual phase in which the endometrial biopsy was performed. [ 8 ], [ 9 ]

Postpartum endometritis

Postpartum endometritis is the leading cause of puerperal fever in pregnancy.[ 10 ] Its incidence ranges from 1% to 3% in patients without risk factors after a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, increasing to approximately 5% to 6% in the presence of risk factors. [Cesarean section is a significant risk factor, associated with a 5- to 20-fold increased risk of postpartum endometritis compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery. If cesarean section occurs after rupture of the amniotic membrane, the risk is even higher.[ 11 ],[ 12 ] Appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis can reduce the risk of postpartum endometritis, with up to 20% of patients developing the disease without antibiotic prophylaxis.[ 13 ] If untreated, postpartum endometritis can have a mortality rate of up to 17%.[ 14 ]

Causes endometritis

Endometritis primarily results from the ascent of microorganisms from the lower genital tract (i.e., the cervix and vaginal vault) into the endometrial cavity. The specific pathogens that most commonly infect the endometrium vary according to the type of endometritis and are sometimes difficult to identify.

Acute endometritis

In acute endometritis, more than 85% of infectious etiologies are due to sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Unlike chronic and postpartum endometritis, whose causality is associated with multiple microorganisms, the primary microbial etiology of acute endometritis is Chlamydia trachomatis, followed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and BV-associated bacteria.[ 15 ]

Risk factors for acute endometritis include age <25 years, history of STIs, risky sexual behavior such as multiple partners, and having undergone gynecologic procedures such as intrauterine devices or endometrial biopsies. These factors contribute to increased susceptibility to the condition among some people.[ 16 ]

Chronic endometritis

The etiology of chronic endometritis is often unknown. Some studies have shown possible endometrial inflammation associated with noninfectious etiologies (e.g., intrauterine contraceptive devices, endometrial polyps, submucous leiomyomas). However, when the causative agent is identified, it is often a polymicrobial infection consisting of organisms commonly found in the vaginal vault. Additionally, genital tuberculosis can lead to chronic granulomatous endometritis, which is most commonly seen in developing countries.[5] Unlike acute endometritis, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are not the most common causes.[5] The main causative agents identified include:

- Streptococci

- Enterococcus fecalis

- E. coli

- Klebsiella pneumonia

- Staphylococci

- Mycoplasma

- Ureaplasma

- Gardnerella vaginalis

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida species [ 17 ]

Chronic endometritis is associated with several risk factors, including use of intrauterine devices, history of multiple pregnancies, previous abortions, and abnormal uterine bleeding. These factors are important considerations in understanding the potential causes and factors contributing to chronic endometritis.

Postpartum endometritis

During pregnancy, the amniotic sac protects the uterine cavity from infection, and endometritis is rare. As the cervix dilates and the membranes rupture, the potential for colonization of the uterine cavity by microorganisms from the vaginal vault increases. This risk is further increased by the use of instruments and the introduction of foreign bodies into the uterine cavity. Bacteria are also more likely to colonize uterine tissue that has been devitalized or otherwise damaged. [ 18 ] Like intra-amniotic infections, postpartum endometrial infection is polymicrobial, involving both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including:

- Gram-positive cocci: treptococci of groups A and B, staphylococci, enterococci.

- Gram-negative rods: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus.

- Anaerobic microorganisms: Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Peptococcus, Prevotella and Clostridium.

- Others: Mycoplasma, Neisseria gonorrhoeae [ 19 ],

Chlamydia trachomatis is a rare cause of postpartum endometritis, although it is often associated with late onset of disease.[ 20 ] Although rare, severe infections with Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium sordellii, or Clostridium perfringens are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.[ 21 ]

Postpartum endometritis is associated with multiple risk factors, including cesarean section, intrapartum intra-amniotic infection (known as chorioamnionitis), prolonged rupture of membranes or prolonged labor, foreign bodies in the uterus (eg, multiple cervical examinations and invasive fetal monitoring devices), manual removal of the placenta, operative vaginal delivery, and certain maternal factors such as HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. Recognition of these risk factors is critical to the identification and treatment of postpartum endometritis, as they may contribute to the development of this condition and guide preventive measures and treatment strategies.[ 22 ]

Pathogenesis

Acute endometritis results from an ascending infection from the cervix and vaginal vault, most commonly caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Endocervical infections disrupt the barrier function of the endocervical canal, allowing infection to ascend.

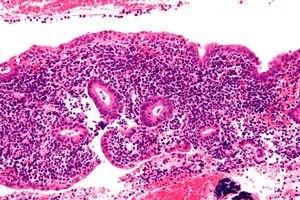

In contrast, chronic endometritis is characterized by infection of the endometrium with microorganisms not necessarily associated with concurrent colonization of the cervix or vagina. The microbial infection results in an immune response and chronic inflammation with significant endometrial stromal plasma cell infiltrates and development of micropolyps.[ 23 ] There is also an increase in interleukin-1b and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which increases estrogen synthesis in endometrial glandular cells. This increased estrogen synthesis may be associated with micropolyps, which are frequently observed on hysteroscopic examination in patients diagnosed with chronic endometritis.

In postpartum endometritis, rupture of the membranes allows bacterial flora from the cervix and vagina to enter the endometrial lining.[4] These bacteria are more likely to colonize uterine tissue that has been devitalized, bleeding, or otherwise damaged (such as during a cesarean section). These bacteria can also invade the myometrium, causing inflammation and infection.

Symptoms endometritis

The clinical diagnosis of acute and postpartum endometritis is based on characteristic symptoms and examination findings; chronic endometritis is often asymptomatic and usually requires histologic confirmation. Clinical histories and symptoms may overlap among the different types of endometritis and differential diagnoses; however, some clinical features are more associated with one type of endometritis than others. Therefore, a thorough history is essential to making an accurate diagnosis. Clinicians taking the history should also attempt to identify common risk factors for PID (eg, multiple sexual partners, history of STIs) and evidence of a differential diagnosis based on a thorough obstetric and sexual history.

Acute endometritis

Symptoms characteristic of acute endometritis include sudden onset of pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and vaginal discharge, which most commonly occur in sexually active individuals, although patients may also be asymptomatic. Depending on the severity of the disease, systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise may also be present, although these are often absent in milder cases. Additional symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding (eg, postcoital, intermenstrual, or heavy menstrual bleeding), dyspareunia, and dysuria.[ 24 ] Symptoms secondary to perihepatitis (eg, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome), tubo-ovarian abscess, or salpingitis may occur in patients with PID, including right upper quadrant pain and lower abdominal pain.

Chronic endometritis

Patients with chronic endometritis often have a history of recurrent miscarriage, repeated implantation failure, and infertility. Chronic endometritis is often asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they are usually nonspecific, with abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic discomfort, and leucorrhoea being the most common complaints.

Postpartum endometritis

The key clinical feature of postpartum endometritis is fever following a recent delivery or miscarriage. Early-onset disease occurs within 48 hours of delivery, and late-onset disease occurs up to 6 weeks postpartum. Symptoms that support the diagnosis include uterine tenderness, significant lower abdominal pain, foul-smelling purulent lochia, and subinvolution of the uterus.[22] Generalized symptoms such as malaise, headache, and chills may also be present.

Where does it hurt?

Complications and consequences

Acute endometritis, especially associated with PID, can lead to infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy. Additionally, ascending infection may develop into a tubo-ovarian abscess.[ 25 ] Complications of chronic endometritis include fertility problems (eg, recurrent miscarriage and recurrent implantation failure) and abnormal uterine bleeding. Approximately 1% to 4% of patients with postpartum endometritis may have complications such as sepsis, abscesses, hematomas, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, and necrotizing fasciitis. Surgery may be required if the infection has resulted in a collection of draining fluid.

Diagnostics endometritis

Studies 1, 2, 3, 5 are carried out on all patients, 4, 6 - if technically possible and if there is doubt about the diagnosis.

- Thermometry. In mild form, the body temperature rises to 38–38.5 °C, in severe form, the temperature is above 39 °C.

- Clinical blood test. In mild form, the number of leukocytes is 9–12×10 9 /l, a slight neutrophilic shift to the left in the white blood cell count is determined; ESR is 30–55 mm/h. In severe form, the number of leukocytes reaches 10–30×10 9 /l, a neutrophilic shift to the left, toxic granularity of leukocytes are detected; ESR is 55–65 mm/h.

- Ultrasound of the uterus. It is performed on all women in labor after spontaneous labor or cesarean section on the 3rd-5th day. The volume of the uterus and its anteroposterior size are increased. A dense fibrinous coating on the walls of the uterus, the presence of gas in its cavity and in the area of ligatures are determined.

- Hysteroscopy. There are 3 variants of endometritis according to the degree of intoxication of the body and local manifestations:

- endometritis (whitish coating on the walls of the uterus due to fibrinous inflammation);

- endometritis with necrosis of decidual tissue (endometrial structures are black, stringy, slightly protruding above the uterine wall);

- endometritis with retention of placental tissue, more common after childbirth (a lumpy structure with a bluish tint sharply outlines and stands out against the background of the walls of the uterus).

A number of patients are diagnosed with a tissue defect in the form of a niche or passage - a sign of partial divergence of the sutures on the uterus.

- Bacteriological examination of aspirate from the uterine cavity with determination of sensitivity to antibiotics. Non-spore-forming anaerobes (82.7%) and their associations with aerobic microorganisms predominate. Anaerobic flora is highly sensitive to metronidazole, clindamycin, lincomycin, aerobic flora - to ampicillin, carbenicillin, gentamicin, cephalosporins.

- Determination of the acid-base balance of lochia. Endometritis is characterized by pH < 7.0, pCO2 > 50 mm Hg, pO2 <30 mm Hg. Changes in these parameters precede clinical manifestations of the disease.

Screening

In order to identify women in labor with subinvolution of the uterus, who are at risk of developing postpartum endometritis, an ultrasound examination is performed on the 3rd–5th day after delivery.

What do need to examine?

How to examine?

Differential diagnosis

In addition to acute endometritis, the differential diagnosis of pelvic pain includes ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhagic or ruptured ovarian cyst, ovarian torsion, endometriosis, tubo-ovarian abscess, acute cystitis, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal causes (eg, appendicitis, diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome).

Common symptoms of chronic endometritis are often abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) or fertility problems. The differential diagnosis of irregular bleeding is broad. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends classifying abnormal uterine bleeding according to the PALM-COEIN system, which is an acronym that stands for polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, malignancies, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial causes (eg, acute or chronic endometritis), iatrogenic (eg, anticoagulants, hormonal contraceptives), and not yet classified.[ 26 ] Infertility also has a broad differential that includes uterine factors, tubal factors, ovulatory or hormonal dysfunction, chromosomal problems, and male factor etiologies.[ 27 ]

In patients with puerperal fever, the differential diagnosis includes surgical site infection, UTI, pyelonephritis, mastitis, pneumonia, sepsis, peritonitis, and septic pelvic thrombophlebitis.

Who to contact?

Treatment endometritis

The goal of endometritis treatment is to remove the pathogen, relieve symptoms of the disease, normalize laboratory parameters and functional disorders, and prevent complications of the disease.

Acute endometritis

The CDC recommends several different antibiotic regimens.[ 28 ],[ 29 ] The following oral regimens are recommended for mild to moderate cases that can be treated on an outpatient basis.

- Option 1:

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly once.

- + doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.

- + metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 14 days

- Option 2:

- Cefoxitin 2 g intramuscularly once with probenecid 1 g orally once

- + doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.

- + metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 14 days

- Option 3:

- Other third-generation parenteral cephalosporins (eg, ceftizoxime or cefotaxime)

- + doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.

- + metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 14 days

- Alternative treatment regimens for patients with severe cephalosporin allergy include:

- Levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily or moxifloxacin 400 mg orally once daily (preferred for M. genitalium infections) for 14 days

- + metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 14 days

- Azithromycin 500 mg IV once daily for 1–2 doses, then 250 mg orally daily + metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 12–14 days [28]

Indications for inpatient hospitalization are:

- Tuboovarian abscess

- Failure of outpatient treatment or inability to adhere to or tolerate outpatient treatment

- Severe illness, nausea, vomiting, or oral temperature >101°F (38.5°C)

- The need for surgical intervention (eg, appendicitis) cannot be ruled out .

Inpatient parenteral antibiotics are given until patients show signs of clinical improvement (eg, reduction in fever and abdominal tenderness), usually for 24 to 48 hours, after which they can be transitioned to an oral regimen. Recommended parenteral regimens include:

- Cefoxitin 2 g IV every 6 hours or cefotetan 2 g IV every 12 hours.

- + Doxycycline 100 mg orally or intravenously every 12 hours

Alternative parenteral regimens:

- Ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g IV every 6 hours + doxycycline 100 mg orally or IV every 12 hours

- Clindamycin 900 mg IV every 8 hours + gentamicin IV or IM 3-5 mg/kg every 24 hours

Chronic endometritis

Chronic endometritis is usually treated with doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days. For patients who fail doxycycline therapy, metronidazole 500 mg orally daily for 14 days plus ciprofloxacin 400 mg orally daily for 14 days may be used.

For chronic granulomatous endometritis, anti-tuberculosis therapy is recommended, including:

- Isoniazid 300 mg per day

- + rifampicin 450–600 mg per day

- + ethambutol from 800 to 1200 mg per day

- + pyrazinamide 1200-1500 mg per day

Postpartum endometritis

Most patients should be given intravenous antibiotics, including those with moderate to severe disease, suspected sepsis, or post-caesarean endometritis. A Cochrane review of antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis identified the following regimen of clindamycin and gentamicin as the most effective:

- Gentamicin 5 mg/kg IV every 24 hours (preferred) or 1.5 mg/kg IV every 8 hours or + clindamycin 900 mg IV every 8 hours

- If group B strep is positive or signs and symptoms do not improve within 48 hours, add any of the following:

- Ampicillin 2 g intravenously every 6 hours or

- Ampicillin 2 g intravenously loading dose, then 1 g every 4–8 hours.

- Ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g intravenously every 6 hours

For those who do not improve within 72 hours, clinicians should expand the differential diagnosis to include other infections such as pneumonia, pyelonephritis, and pelvic septic thrombophlebitis. Intravenous antibiotics should be continued until the patient remains afebrile for at least 24 hours, along with pain relief and resolution of leukocytosis. There is no substantial evidence that continuing oral antibiotics after clinical improvement significantly improves patient-centered outcomes. [ 30 ] An oral antibiotic regimen may be carefully considered in patients with mild symptoms detected after hospital discharge (eg, late-onset postpartum endometritis).

Forecast

Without treatment, the mortality rate for postpartum endometritis is approximately 17%. However, in well-developed countries, the prognosis is usually excellent with appropriate treatment. Acute endometritis itself has an excellent prognosis; however, it is often present with salpingitis, which significantly increases the risk of tubal infertility. Evidence suggests that fertility outcomes may improve significantly after treatment of chronic endometritis. For example, in a study of day 3 fresh embryo transfer cycles, live birth rates were significantly higher in treated patients compared with untreated patients, approximately 60% to 65% versus 6% to 15%, respectively. Another study found that in patients with recurrent miscarriage and chronic endometritis, the live birth rate increased from 7% before treatment to 56% after treatment.[ 31 ]