All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Why do nonsmoking lung cancer patients have worse outcomes?

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

">

">Researchers from University College London (UCL), the Francis Crick Institute and AstraZeneca have discovered the reason why targeted treatments for non-small cell lung cancer fail to work in some patients, particularly those who have never smoked.

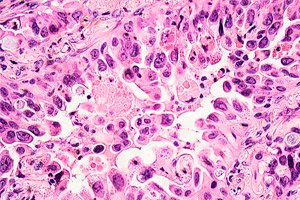

A study published in Nature Communications shows that lung cancer cells with two specific genetic mutations are more likely to double their genomic load, which helps them survive treatment and develop resistance to it.

In the UK, lung cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer death. Around 85% of patients with lung cancer have non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and it is the most common type in patients who have never smoked. Considered separately, lung cancer in "never smokers" is the fifth most common cause of cancer death worldwide.

The most common genetic mutation found in NSCLC involves the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene, which allows cancer cells to grow faster. It is found in around 10-15% of NSCLC cases in the UK, particularly in patients who have never smoked.

Survival depends on the stage of the cancer, and only about a third of patients with stage IV NSCLC and an EGFR mutation survive for three years.

Lung cancer treatments that target this mutation, known as EGFR inhibitors, have been around for more than 15 years. However, while some patients’ cancer tumours shrink with EGFR inhibitors, other patients, particularly those with an additional mutation in the p53 gene (which plays a role in suppressing tumours), do not respond to the treatment and have much worse survival rates. But scientists and clinicians have been unable to explain why this is so.

To find the answer, the researchers reanalysed data from trials of AstraZeneca’s newest EGFR inhibitor, osimertinib. They looked at baseline scans and the first follow-up scans taken after several months of treatment in patients with an EGFR mutation or an EGFR and p53 mutation.

The team compared each tumor in the scans, many more than were measured in the original study. They found that in patients with only EGFR mutations, all of the tumors shrank in response to treatment. But in patients with both mutations, while some tumors shrank, others grew, evidence of rapid resistance to the drug. This type of response, where some but not all areas of cancer shrink in response to drug treatment within a single patient, is known as a “mixed response,” and it presents a challenge for oncologists caring for patients with cancer.

To investigate why some tumors in these patients were more susceptible to drug resistance, the team then examined a mouse model with both EGFR and p53 mutations. They found that within the resistant tumors in these mice, many more cancer cells had doubled their genomic load, giving them extra copies of all their chromosomes.

The researchers then treated lung cancer cells in the lab, some with just one EGFR mutation and others with both mutations, with an EGFR inhibitor. They found that after five weeks of exposure to the drug, a significantly higher percentage of cells with both the double mutation and the double genomic burden had multiplied into new cells that were resistant to the drug.

Professor Charles Swanton, from University College London and the Francis Crick Institute, said: "We have shown why having a p53 mutation is associated with worse survival in patients with non-smoking lung cancer, which is a combination of EGFR and p53 mutations allowing the genome to be duplicated. This increases the risk of developing drug-resistant cells through chromosome instability."

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer are already tested for EGFR and p53 mutations, but there is currently no standard test to detect the presence of whole genome duplication. Researchers are already looking at ways to develop a diagnostic test for clinical use.

Dr Crispin Highley, from University College London and consultant oncologist at University Hospitals London, said: "Once we can identify patients with EGFR and p53 mutations whose tumours display whole-genome duplications, we will be able to treat these patients more selectively. This could mean more intensive surveillance, earlier radiotherapy or ablation to target resistant tumours, or earlier use of combinations of EGFR inhibitors such as osimertinib with other drugs including chemotherapy."