All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

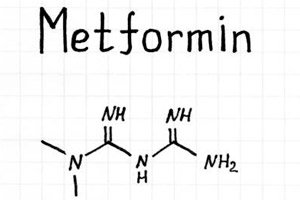

Study advances understanding of metformin's effect on fetus

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

">

">A study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology shows that when the drug metformin is given to a mother during pregnancy, fetal growth is slowed, including delayed kidney maturation, which is associated with an increased risk of obesity and insulin resistance in childhood.

Metformin, prescribed to 50 million Americans each year, has long been used outside of pregnancy to control blood sugar levels, but is now widely prescribed to pregnant women to reduce complications associated with prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, and obesity. Although metformin is effective in controlling a pregnant woman’s blood sugar and reducing the likelihood of having a large-for-date baby, little was known about the drug’s long-term effects on the newborn.

"It is known that if a pregnant woman is obese and has diabetes, her baby is more likely to develop obesity and diabetes. Because metformin is widely used in pregnant women, it is important for us to understand whether the drug is beneficial for babies in the long term or has unintended consequences," said study co-author Jed Friedman, Ph.D., vice chancellor for diabetes programs at the University of Oklahoma and director of the Harold Hamm Diabetes Center.

The results of the study show that metformin freely crosses the placenta and accumulates in the kidneys, liver, intestine, placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetal urine, where its concentration was almost the same as in maternal urine. This accumulation is associated with delayed growth of the kidneys, liver, skeletal muscle, heart, and fat deposits that support the abdominal organs, leading to decreased fetal body weight.

Because fetal growth restriction is associated with an increased risk of obesity and insulin resistance in childhood, the baby may face additional health risks, such as cardiovascular problems. The situation is somewhat of a vicious circle: if blood sugar is not controlled during pregnancy, risks arise for both mother and baby, including obesity and diabetes in the growing child. However, metformin itself may pose the same risks, despite its effectiveness in controlling blood sugar and reducing fetal growth.

Historically, studies of drugs during pregnancy have focused on potential harm to the baby, with less emphasis on the infant's growth and metabolism. Although metformin does not cause birth defects, the fetus also has no way to eliminate the drug from its body.

"Many drugs undergo 'first-pass' metabolism, in which they are first absorbed by the liver, which reduces their concentration before being distributed throughout the body. However, metformin does not undergo the first-pass effect; it is transported across the placenta, exposing the fetus to the adult dose," Friedman explained.

The research team also looked at whether maternal diet affected fetal metformin levels. Half of the subjects were fed a normal diet with 15% of calories from fat, and the other half were fed a high-fat diet with 36% of calories from fat. The results showed that metformin levels were not affected by diet.

"This was a small study, and much more research is needed to better understand the effects of metformin on the fetus," Friedman said. "The first 1,000 days — from conception to a child's second year of life — are a key area for us to combat the obesity and diabetes epidemics."