All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Mitochondrial enhancement reverses protein accumulation in aging and Alzheimer's

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

">

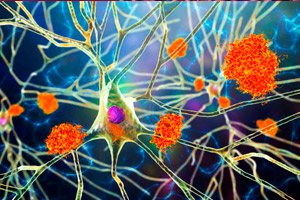

">It has long been known that a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and most other neurodegenerative diseases is the formation of insoluble protein aggregates in the brain. Even during normal aging without disease, insoluble proteins accumulate.

To date, approaches to treating Alzheimer’s disease have not addressed the contribution of protein insolubility as a general phenomenon, but have focused on one or two insoluble proteins. Recently, researchers at the Buck Institute completed a systematic study in worms that paints a complex picture of the relationships between insoluble proteins in neurodegenerative diseases and aging. In addition, the work showed an intervention that can reverse the toxic effects of aggregates by improving mitochondrial health.

"Our findings suggest that targeting insoluble proteins may provide a strategy to prevent and treat a variety of age-related diseases," said Edward Anderton, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Gordon Lithgow's lab and one of the first authors of the study published in the journal GeroScience.

"Our study shows how maintaining healthy mitochondria can combat protein aggregation associated with both aging and Alzheimer's disease," said Manish Chamoli, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Gordon Lithgow and Julie Andersen, and one of the study's first authors. "By improving mitochondrial health, we can potentially slow or reverse these harmful effects, offering new ways to treat both aging and age-related diseases."

The results support the gerontological hypothesis

The strong link between insoluble proteins that contribute to normal aging and disease also supports a broader picture of how aging and related diseases occur.

"We would argue that this work really supports the gerontology hypothesis that there is a common pathway to both Alzheimer's disease and aging itself. Aging causes disease, but the factors that lead to disease occur very early," said Gordon Lithgow, PhD, the Buck Professor, vice president for academic affairs and senior author of the study.

The fact that the team found a core insoluble proteome enriched in numerous proteins that had not been considered before creates new targets for research, Lithgow said. "In some ways, it raises the question of whether we should be looking at what Alzheimer's looks like in very young people," he said.

Beyond Amyloid and Tau

Most Alzheimer’s research so far has focused on the accumulation of two proteins: amyloid beta and tau. But these insoluble aggregates actually contain thousands of other proteins, Anderton said, and their role in Alzheimer’s was unknown. In addition, his lab and others have observed that insoluble proteins also accumulate during the normal aging process without disease. These insoluble proteins from older animals, when mixed with amyloid beta in a test tube, accelerate the aggregation of amyloid.

The team asked themselves what the connection was between the accumulation of Alzheimer's aggregates and aging without the disease. Focusing on amyloid beta, they used a strain of the microscopic worm Caenorhabditis elegans, long used in aging research, that had been genetically modified to produce human amyloid protein.

Anderton said the team suspected that amyloid beta might cause some degree of insolubility in other proteins. "We found that amyloid beta causes massive insolubility, even in very young animals," Anderton said. They found that there is a subset of proteins that appear to be very vulnerable to insolubility, either due to the addition of amyloid beta or during the normal aging process. They called this vulnerable subset the "core insoluble proteome."

The team also demonstrated that the core of the insoluble proteome is filled with proteins that have already been linked to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases beyond Alzheimer's, including Parkinson's, Huntington's, and prion diseases.

"Our study shows that amyloid may act as an engine of this normal age-related aggregation," Anderton said. "We now have clear evidence, I think for the first time, that both amyloid and ageing affect the same proteins in similar ways. It's quite possibly a vicious cycle where ageing causes insolubility, and amyloid beta also causes insolubility, and they just reinforce each other."

The amyloid protein is highly toxic to the worms, and the team wanted to find a way to reverse that toxicity. “Because hundreds of mitochondrial proteins become insoluble both during aging and after amyloid beta expression, we thought if we could improve the quality of mitochondrial proteins with a compound, then maybe we could reverse some of the negative effects of amyloid beta,” Anderton said. That’s exactly what they found using urolithin A, a natural metabolite produced in the gut when we eat raspberries, walnuts, and pomegranates that’s known to improve mitochondrial function: It significantly delayed the toxic effects of amyloid beta.

"What was clear from our data was the importance of mitochondria," Anderton said. One takeaway, the authors said, is that mitochondrial health is critical to overall health. "Mitochondria have a strong connection to aging. They have a strong connection to amyloid beta," he said. "I think ours is one of the few studies that shows that the insolubility and aggregation of these proteins may be a link between the two processes."

"Because mitochondria are so important to all of this, one way to break the cycle of decline is to replace damaged mitochondria with new mitochondria," Lithgow said. "And how do you do that? Exercise and eat a healthy diet."