All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

How does the immune system prepare for breastfeeding?

Last reviewed: 03.08.2025

">

">Of the 3.6 million babies born in the United States each year, about 80% begin breastfeeding within the first month of life. Breastfeeding is known to provide benefits to both mother and baby: it reduces the mother’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure while providing nutrition and immune support to the baby. But because pregnancy and lactation have traditionally been understudied, we still don’t fully understand the mechanisms behind these benefits.

Immunologists at the Salk Institute are changing that — starting with the migration map of immune cells before and during lactation. Using both animal experiments and breast milk and human tissue samples, the scientists found that T cells, a type of immune cell, accumulate in abundance in the mammary glands during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Some of them also migrate from the gut, presumably providing support to both mother and baby.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Immunology, could explain the immune benefits of breastfeeding, provide insight into solutions for mothers who cannot breastfeed, and help develop diets that improve milk composition and production.

“When we started looking at how immune cells change during pregnancy and lactation, we found a lot of interesting things – particularly the fact that there is a dramatic increase in immune cells in breast tissue during lactation, and that this increase is dependent on microbes,” explains Associate Professor Deepshika Ramanan, lead author of the study.

What we already knew: Babies get bacteria and antibodies from their mother's milk

Most breastfeeding research has focused on the relationship between milk composition and infant health. Such studies, including Ramanan’s previous ones, have shown that babies receive important gut bacteria and antibodies from their mothers through milk, laying the foundation for the infant’s immune system. But the changes in the mother’s body during this period remain poorly understood.

Some aspects of the mammary immune environment have been predicted by the composition of milk. For example, the presence of antibodies in milk indicates the presence of B cells that produce them. However, few have examined immune cell activity directly in mammary tissue.

What's New: Maternal Gut Microbes Boost Breast Immunity

“The exciting thing is that we not only found more T cells in the breast, but some of them clearly came from the gut,” said Abigail Jaquish, a graduate student and first author of the paper.

“They’re likely supporting the breast tissue in the same way they normally support the intestinal lining.”

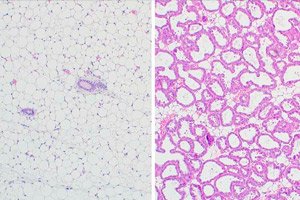

The study began by examining mammary tissue from mice at different stages before and after lactation. The scientists found that three types of T cells, CD4⁺, CD8αα⁺ and CD8αβ⁺, increase sharply during this time.

This surprised the team because these T cells belong to a special class of immune cells called intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). These cells live in mucous-lined tissues, such as the intestines and lungs, that are exposed to external influences. IELs act as “guardians” – they are constantly present in the tissues, ready to respond immediately to a threat.

In the mammary gland, these T cells lined up along the epithelium in a similar way to how they do in mucous membranes, and carried proteins on their surface that are characteristic of intestinal T cells, indicating that T cells migrated from the intestine to the mammary glands.

In this way, the mother’s body transfers the mammary gland from “internal” tissue to “mucous” tissue, since during feeding it comes into contact with the external environment: microbes from the mother’s skin and the baby’s mouth.

Does the same thing happen in humans?

An analysis of a database of human breast tissue and breast milk samples (from the Human Milk Institute at the University of California, San Diego) found that similar T cells also increase in women during lactation.

The scientists then returned to the mouse model to ask a final question:

Do microbes influence these T cells in the mammary gland in the same way as they do in the gut?

It turns out yes.

Mice living in a normal microbial environment had significantly higher levels of all three types of T cells in their mammary glands than mice in germ-free conditions. This suggests that the mother’s microbes activate T cell production, which in turn boosts the immune defenses of the mammary tissue.

So what do we know now:

- Microbes Boost Immune Response in Breasts

- T cells migrate from the intestine to the site of lactation

- The mammary gland becomes a mucous tissue during feeding, adapting to external influences

What's next? How are the gut and breast connected, and how does this impact generational health?

“We now know much more about how the mother’s immune system changes during this critical period,” Ramanan says.

“This opens up the possibility of investigating the direct impact of these immune cells on the health of both mother and baby.”

Scientists assume that hormones regulate all these changes, the purpose of which is to protect the mother from external threats and infections. But how exactly this affects lactation, milk composition and health is the next big question for research.

“We’re just at the beginning,” adds Jaquish. “If we see a connection between the gut and the mammary gland, what other systems in the body might be interacting? And what else influences the composition of the milk we pass on to our offspring?”

Understanding changes in the mother's immune system during pregnancy and lactation can impact intergenerational health as immune and microbial components are passed from mother to child over and over again.

These findings could also help women who cannot breastfeed – for example, by developing therapies that stimulate milk production or improved formulas that can provide similar immune support.

As the connection between the gut and breast becomes clearer, scientists may be able to recommend diets in the future that promote maternal health and optimal milk quality.