All iLive content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure as much factual accuracy as possible.

We have strict sourcing guidelines and only link to reputable media sites, academic research institutions and, whenever possible, medically peer reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses ([1], [2], etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

If you feel that any of our content is inaccurate, out-of-date, or otherwise questionable, please select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Congenital anomalies are ten times more common in children with neurodevelopmental disorders

Last reviewed: 02.07.2025

">

">Children with neurodevelopmental disorders report congenital anomalies, such as heart and/or urinary tract defects, at least ten times more often than other children.

This is one of the results of an analysis conducted by Radboud University Medical Center based on data from more than 50,000 children. Thanks to this new database, it is now much clearer which health problems are associated with a particular neurodevelopmental disorder and which are not. The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Two to three percent of the population has neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism or intellectual disability. These disorders are often accompanied by other health problems or are part of an underlying syndrome, requiring additional medical attention for the child. Until now, it was not known how often these additional health problems occur.

"It's strange," says clinical geneticist Bert de Vries. "Because it interferes with the proper care of this special group of children."

De Vries and colleagues collected medical data from more than 50,000 children with neurodevelopmental disorders. They started with data from nearly 1,500 children with neurodevelopmental disorders who had visited the Clinical Genetics Department at Radboud University Medical Center over the past decade.

"However, this was a relatively small group of children. To draw conclusions about the entire group, larger numbers are needed," explains De Vries.

So medical researcher Lex Dingemans then searched the entire medical literature on neurodevelopmental disorders. "It was a huge task, starting with the first relevant paper in 1938 by Professor Penrose of London," says Dingemans.

He found more than 9,000 published studies. Ultimately, about seventy articles contained enough useful, high-quality data to identify additional health problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders, creating a database of more than 51,000 children.

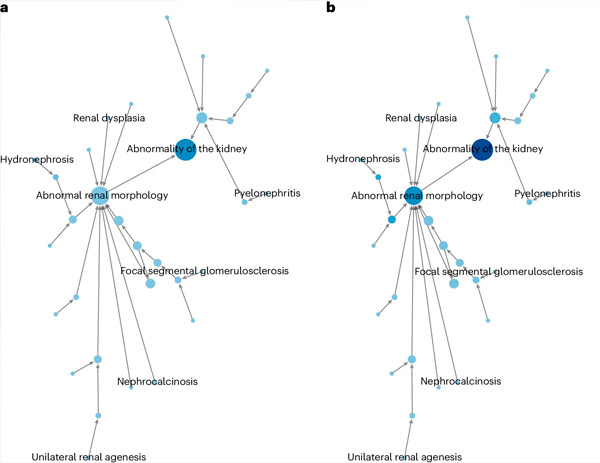

Analysis of this data provided new insights. First, it found that children with neurodevelopmental disorders have at least ten times more congenital anomalies than other children in the general population, such as abnormalities of the heart, skull, urinary tract, or hip. In addition, the database maps the medical consequences of new syndromes.

Dingemans explains: "For many syndromes that cause neurodevelopmental disorders, there is a question of to what extent other health problems are associated with them. Now that we know the numbers of these problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders, we can much better determine what is actually part of the syndrome and what is not." This opens up opportunities for better management or even treatment of children.

Neurodevelopmental disorders are genetic in nature. Currently, more than 1,800 genes are known to be the cause.

"To understand these genetic causes well, we use global databases that pool DNA data from more than 800,000 people," says Lisenka Vissers, professor of translational genomics. "Our database complements that. It allows researchers around the world to link genetic knowledge to the occurrence of specific health problems in neurodevelopmental disorders."